Some years ago I went to a lecture given by Professor David MacKay, who in addition to being a distinguished physicist (he's professor of natural philosophy at Cambridge) is also the chief scientific officer of the Department of Energy and Climate Change. He was talking about his book, Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air, in which he subjects the case for wind power to some searching criticism. In the Q&A after the lecture a member of the audience asked him why he was so hostile to wind power. "I'm not hostile to wind power," he replied. "I'm just pro-arithmetic."

It was a terrific riposte and it made the audience laugh. But actually it captured in a nutshell what's wrong with most of our public discourse and almost all of our journalism: it's innumerate. One of the best arguments for having kids study physics is not that it prepares them for careers hunting Higgs bosons but that it inculcates in them an instinct for quantitative analysis. At a symposium that MacKay organised many years ago I watched a physicist examine the global demand for energy implied by the UN's predictions for population growth – and then go on to analyse the proposition that nuclear energy could close the energy gap without increasing carbon dioxide emissions. With a set of easily comprehensible, back-of-envelope calculations, he showed that the gap could indeed be bridged – by commissioning a new nuclear station every two weeks from now until 2070. End of argument.

Note that we're not talking fancy mathematics here: no quadratic or nonlinear differential equations were required. Just plain, simple arithmetic – together with a distinctive mindset which says that the way to examine an issue is to take particular policy propositions, find some data that would enable one to assess their implications, costs and benefits, and then do some calculations.

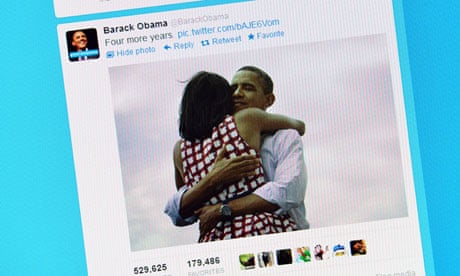

Which brings us to the Obama election campaign. In 2008, it was obvious that his people were significantly more internet-savvy than the McCain-Palin crowd. (Not that that would have been too difficult.) Obama harnessed the internet to crowdsource fundraising, for example, and used social media to get the vote out. And he used YouTube to bypass the TV networks and get his message directly to voters – as with A More Perfect Union, his Philadelphia speech tackling the problems raised for him by the inflammatory views of his pastor, Jeremiah Wright. A More Perfect Union is a long (37-minute), serious speech which would have been reduced to a set of soundbites by the TV networks. By using YouTube, Obama ensured that millions of US voters heard his unexpurgated version.

But none of this was rocket science. The interesting question this time was what the Obama crowd would do next. Now we know, thanks to a fascinating piece of reporting by Michael Scherer in Time, published just after the election result was clear. Basically, it comes down to numbers. The campaign was run by Jim Messina, the White House deputy chief of staff. When Messina took on the campaign job, he said: "We are going to measure every single thing." It turns out that he meant it. He assembled a huge data analytics department, and installed as "chief scientist" an expert in crunching large data sets for supermarkets. Messina's "quants" were installed in a windowless room, forbidden to talk to anyone and told to do their stuff.

The 2008 Obama team had gathered a huge amount of data on voters during the campaign, but it was held in a set of separate data silos. The first thing the new team did was to combine the silos into a single enormous database. How they coped with the security issues raised by this strategy isn't discussed by Scherer, and should be keeping someone awake at night, but it meant that the Obama campaign had an enormous data set which could be mined for (a) small donations (which totalled over $1bn in the end) and (b) insights about voter preferences and behaviour which could be used to try various kinds of experiment. They could ask a question of the data like: what kind of celebrity supporter had the biggest drawing power for professional women aged between 40 and 49 in California? Answer: George Clooney. Who might have comparable gravitational pull on the same demographic group on the east coast? Answer: Sarah Jessica Parker. And so on.

Obama's re-election is a compelling demonstration of what can be done when you apply quantitative analysis to large data sets. James Carville's famous phrase – "The economy, stupid" – has been superseded. Now it's the data, stupid.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion