According to figures out yesterday, American consumer debt is continuing its four-year-long fall, while consumer confidence has hit its highest level in nearly five years. The most recent quarter’s GDP numbers were positive, and forecasters expect slow but steady growth if the fiscal cliff is avoided. By contrast, most of Europe now endures a recession.

Of course, that’s partly because the continent remains mired in its financial crisis. But it also reflects very different attitudes toward macroeconomic management in America and Europe.

While many countries in Europe have either sought austerity or had it forced upon them, the United States has stubbornly kept both its fiscal and its monetary policy fairly loose. The result has been steady if uninspiring growth. This can’t last, say critics, pointing to America’s continued deficits and rising debt load. Yet interest rates and yields on US debt remain low.

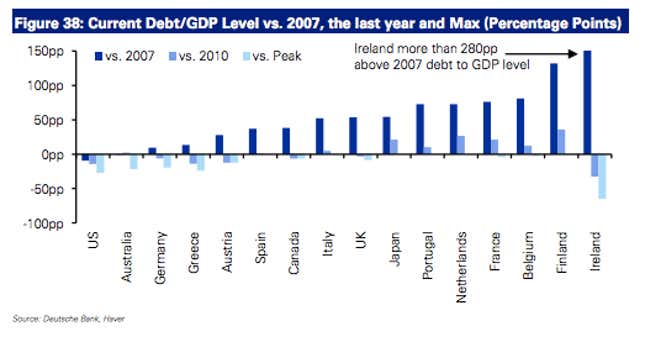

The reason the markets, and not the critics, might be right is in the above graph. It’s from a September report by Deutsche Bank’s fixed-income research team called “A Journey Into the Unknown” (PDF—see page 31) and it shows the change in overall debt—which means not just government, but also financial, corporate and household debt—in relation to GDP since 2007, 2010 and the previous peak debt, for various developed nations. What stands out is that while most of them have increased their debt in toto since at least one of those three points in time, the US is the only country on the list to have stabilized it.

Just stopping the total debt from growing may not seem like much to brag about. But the picture changes when you look at what the debt is made up of.

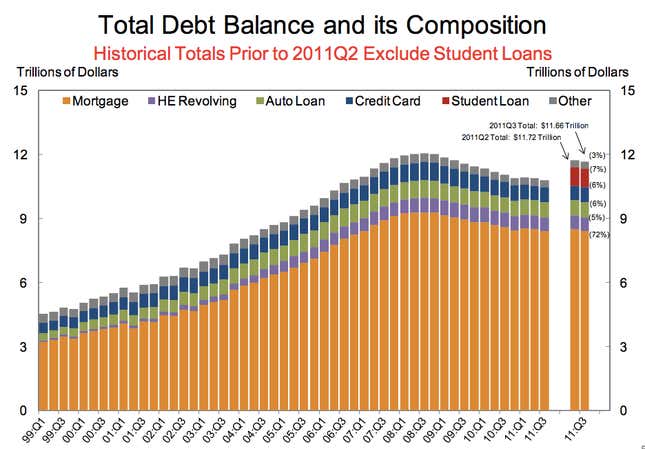

Financial crises based on asset bubbles, like the one that wracked the globe in 2008, leave a fairly serious hangover of debt (underwater mortgages, credit card bills to be paid on lower salaries, etc.) to be cleared away even after the fires are put out and everything’s marked to market. Clearing credit channels and restoring demand to pre-crisis levels is far more difficult following these sorts of recessions, a point fairly well established by Harvard economists Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart. This helps explain why growth has been so slow in the developed world where these bubbles were found.

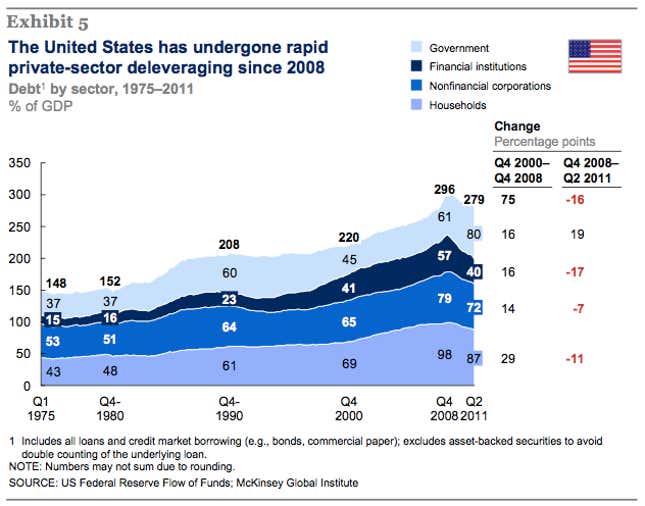

But in the US, in theory at least, the government has been taking on debt so that consumers and businesses may shed it. The graph below, from a January McKinsey report on rich-world debt, shows how. Government stimulus measures and transfer payments allow consumers to deleverage. In return, debt accumulates with the public sector, which borrows more cheaply and has a longer time horizon for managing debt than people do. That helps explain why the American economy has been expanding, thanks in part to more consumer demand, even as public debt has swollen to levels unsustainable in the long term. It’s an invisible bailout.

In Europe, meanwhile, an insistence on public austerity has left businesses and consumers trying to reduce their debt without government help and in a more hostile economic environment. True, US growth is still anemic. And the country will have to pay the price of its borrowing one day. But in the meantime, the American strategy of stimulus has offered some near-term flexibility and a window to deal with structural problems. The euro zone, by contrast, remains weighed down by them.